Our interactive VBA tutorial is perfect for beginners or experienced users looking to brush up on their skills. Create a free account to save your progress and much more!

This VBA tutorial will teach you the basics of using VBA with Excel. No prior coding experience? No problem! Because VBA is integrated into Excel, coding is very intuitive. Beginners can learn VBA very quickly!

The tutorial is 100% free. No sign-up is required, but by creating an account you'll be able to save your tutorial progress, and receive many other VBA resources for free!

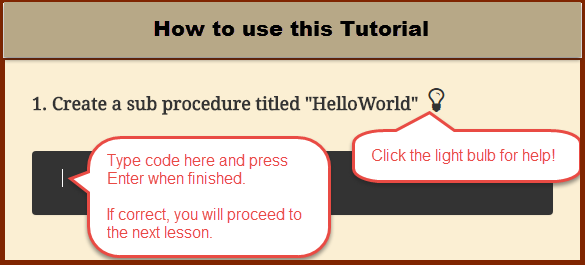

The tutorial contains 100 exercises spread across 10 chapters. The course is meant to replicate a "boot camp" experience where you learn very quickly by immediately completing exercises related to the course topics.

Each exericse has a "Hint" button, showing you the correct answer. So if you're stuck, you can easily see the correct answer.

The course contents are listed below:

| Chapter | Progress | Complete? |

|---|---|---|

1. VBA BasicsIntroduction to the basics of working with VBA for Excel: Subs, Ranges, Sheets, & More |

Login to See | Login to See |

2. VariablesDeclaring variable types, assigning object and non-object variables |

Login to See | Login to See |

3. Conditional LogicComparing values and conditions, if statements and select cases |

Login to See | Login to See |

4. LoopsRepeat processes with For loops and Do While or Do Until Loops |

Login to See | Login to See |

5. Adv Cell ReferencingWorking with cells, rows, and columns to copy/paste, count, find the last used row or column, assigning formulas, working with sheets |

Login to See | Login to See |

6. Msg & Input BoxesCommunicate with the end-user with message boxes and take user input with input boxes |

Login to See | Login to See |

7. EventsTrigger procedures to run when certain “eventsâ happen like activating a worksheet, or changing cell values |

Login to See | Login to See |

8. SettingsSpeed up your code and improve the user experience |

Login to See | Login to See |

9. Adv ProceduresPublic variables, functions, and passing variables to other procedures. |

Login to See | Login to See |

10. ArraysProgrammatically work with series of values without needing to interact with Excel objects. |

Login to See | Login to See |

We converted our Interactive VBA Tutorial into a 70 page PDF. The PDF is colorful, easy to navigate, and filled with examples. You'll also receive access to our PowerPoint and Word VBA Tutorials (Access and Outlook coming soon)!

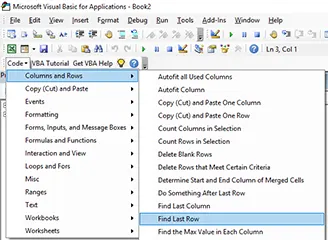

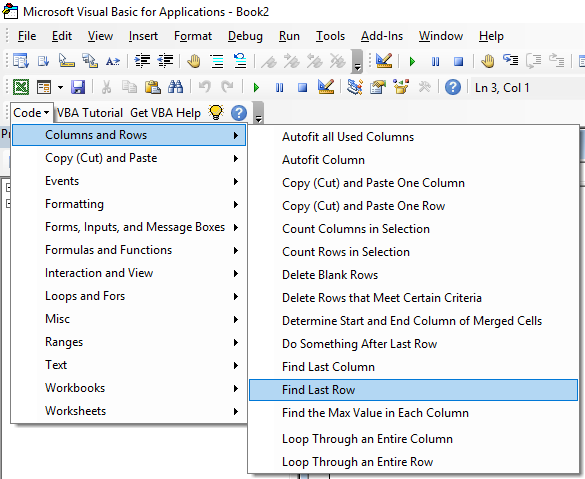

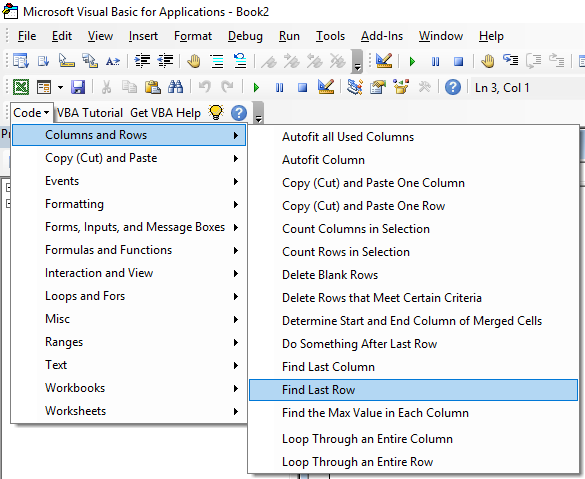

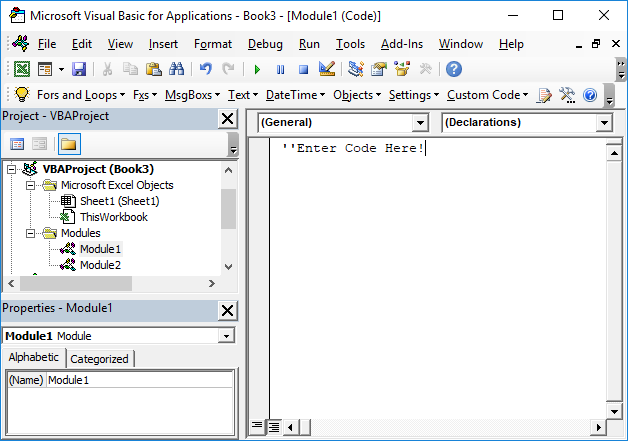

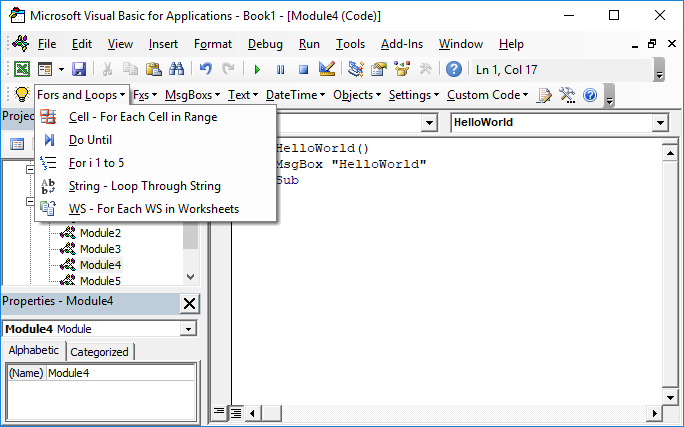

Our free VBA Add-in installs directly into the VBA Editor, giving you access to 150 ready-to-use VBA code examples for Excel.

Simply click your desired code example and it will immediately insert into the VBA code editor.

This is a MUCH simplified version of our premium VBA Code Generator.

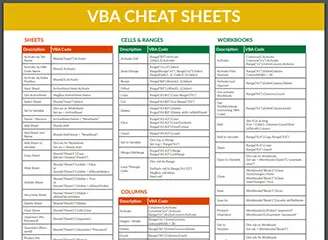

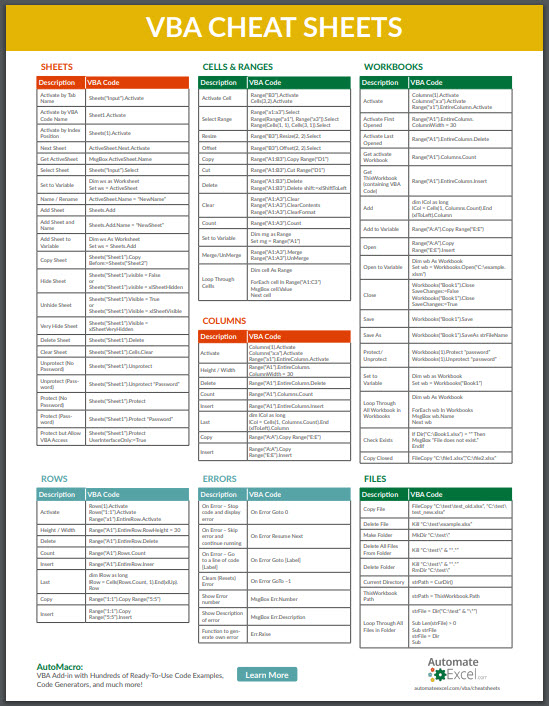

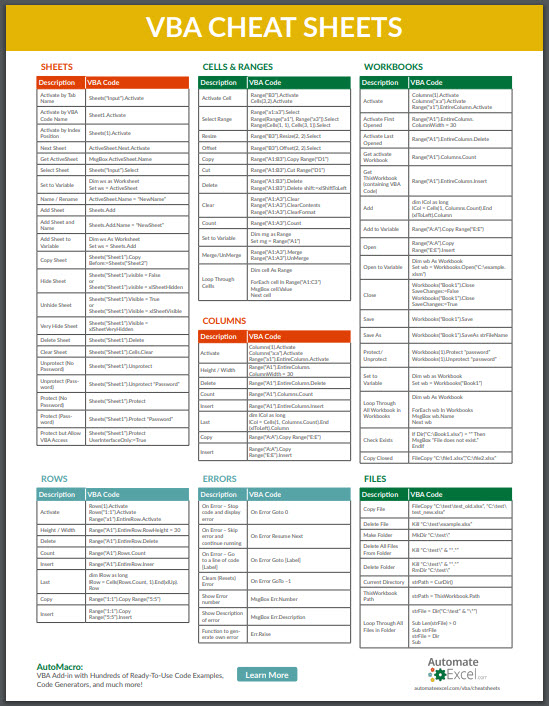

PDF "Cheat Sheet" containing the most commonly used VBA Commands and syntax. Print the PDF or save it to your computer for easy reference!

We converted our Interactive VBA Tutorial into a 70 page PDF. The PDF is colorful, easy to navigate, and filled with examples. You'll also receive access to our PowerPoint and Word VBA Tutorials (Access and Outlook coming soon)!

Our free VBA Add-in installs directly into the VBA Editor, giving you access to 150 ready-to-use VBA code examples for Excel.

Simply click your desired code example and it will immediately insert into the VBA code editor.

This is a MUCH simplified version of our premium VBA Code Generator.

PDF "Cheat Sheet" containing the most commonly used VBA Commands and syntax. Print the PDF or save it to your computer for easy reference!

We converted our Interactive VBA Tutorial into a 70 page PDF. The PDF is colorful, easy to navigate, and filled with examples. You'll also receive access to our PowerPoint and Word VBA Tutorials (Access and Outlook coming soon)!

Our free VBA Add-in installs directly into the VBA Editor, giving you access to 150 ready-to-use VBA code examples for Excel.

Simply click your desired code example and it will immediately insert into the VBA code editor.

This is a MUCH simplified version of our premium VBA Code Generator.

PDF "Cheat Sheet" containing the most commonly used VBA Commands and syntax. Print the PDF or save it to your computer for easy reference!

This VBA tutorial will teach you the basics of using VBA with Excel. No prior coding experience? Don’t worry! Because VBA interacts directly with Excel, coding is very intuitive. Beginners can learn VBA very quickly!

You can create a free account to save your progress by clicking the Create an Account button above. Once you’re signed up, your progress will be saved whenever you leave the app. When you return, you will be prompted to continue where you left off.

You can click "Start the Course" to get started, review the Course Contents below, or below the Course Contents you will find an introductory tutorial covering What is VBA, the Visual Basic Editor, Recording Macros, and more.

Now let's get started:

Note: Creating an account allows you to save your progress. When you reopen this app you will be able to return to the next unanswered question.

Download the PDF version of our Interactive VBA Tutorial! Or VBA Tutorials for other Office Programs!

VBA stands for Visual Basic for Applications - an implementation of Microsoft’s Visual Basic language built into most Microsoft Office applications (in our case, Microsoft Excel). You can program VBA to complete any task that you could manually do while working in Excel or other applications. By using VBA code you can automate repetitive tasks saving valuable time and energy. You can learn more about the background of VBA on Wikipedia.

A Macro is a general term that refers to a set of programming instructions that automates tasks. A VBA Macro is simply a macro created with the VBA programming language.

Practice! First, go through our interactive VBA tutorial to learn the basics. Second, attempt to automate some simple tasks, when you get stuck search online for code examples. You can easily find code examples for almost any VBA task! Copy and paste the code example and adapt as needed.

The Visual Basic Editor is where VBA code is stored:

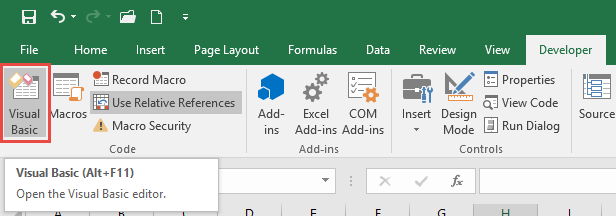

You can access the Visual Basic Editor in the Developer Ribbon:

or with the shortcut ALT + F11.

If you don’t see the Developer Ribbon, you will need to add it (directions in the next section).

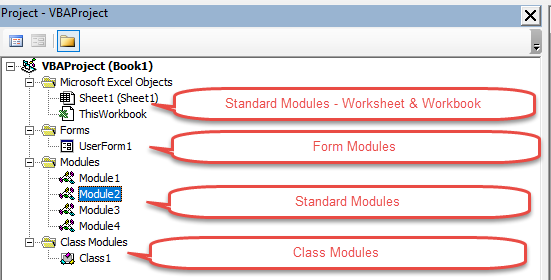

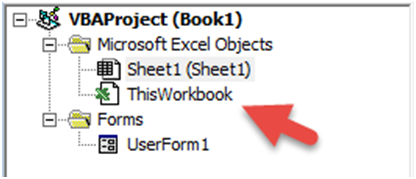

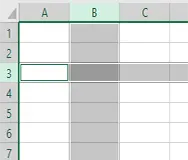

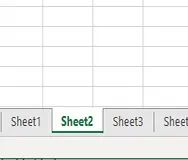

In the Visual Basic Editor you will find the Project Window. This window contains a list of the “modules” for all open workbooks. Modules are where the code is stored. There are three module types:

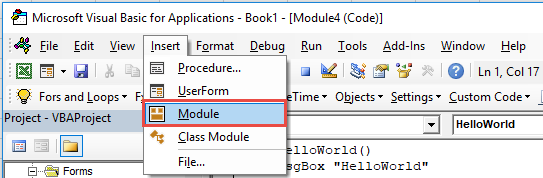

To insert a module, go to the Insert Menu (ALT > I).

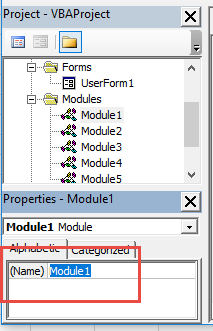

You can (and should) rename Modules in the Properties Window. Renaming modules makes it easier to organize your code. If your VBA project contains more than one module, you should rename the modules.

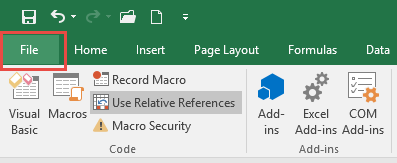

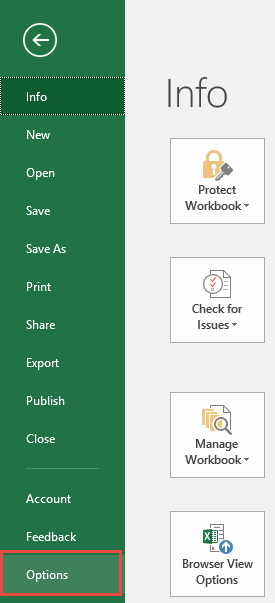

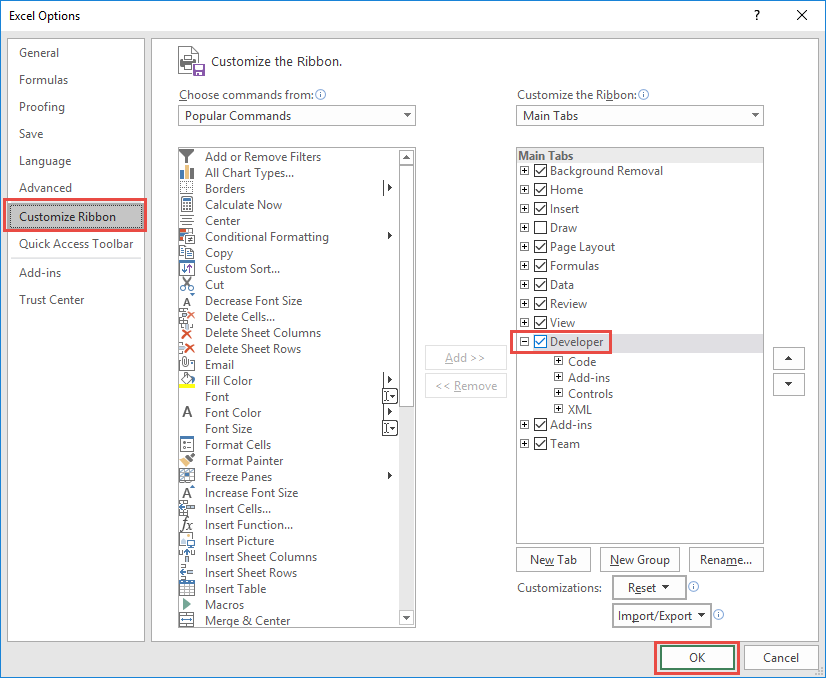

By default, the Developer Ribbon is not visible. You will need to manually turn it on. Follow these steps to enable the Developer Ribbon:

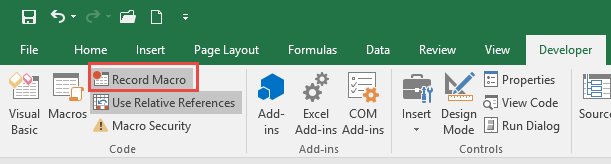

The Macro Recorder allows you to “record” your actions to VBA code. Even if you don’t know one bit of VBA code, you can use the Macro Recorder to create VBA procedures that repeat a series of actions.

Recording a Macro is easy:

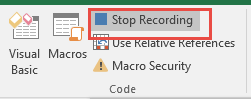

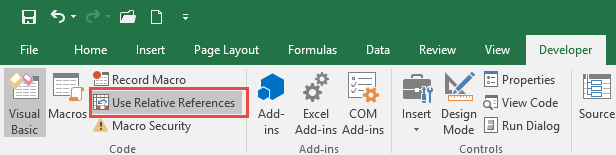

When Recording a Macro there are two options: ‘Use Relative References’ or not.

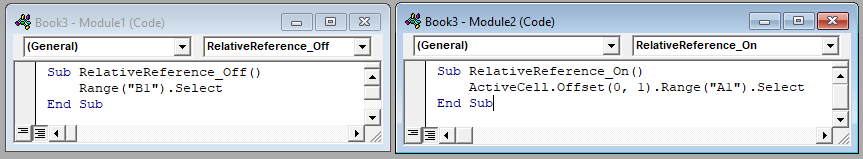

This setting changes how your code is recorded when selecting different cells. With ‘Use Relative References’ turned off, the Macro Recorder will record the actual cell ranges that you select. With it turned on, when using the keyboard to navigate, the Macro Recorder will record "offsets" from the activecell. Here is an example: Suppose you start in cell A1 and press the right arrow. With ‘Use Relative References’ turned off, cell B1 is recorded. With it turned on, Activecell.Offset(1,0) is recorded instead. This makes your code flexible based on whatever cell is selected when you run the Macro:

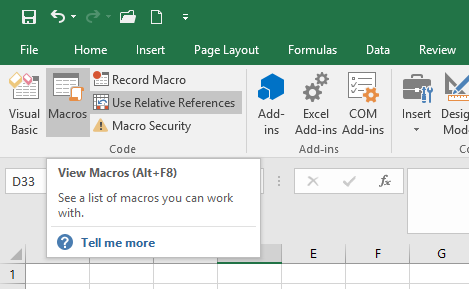

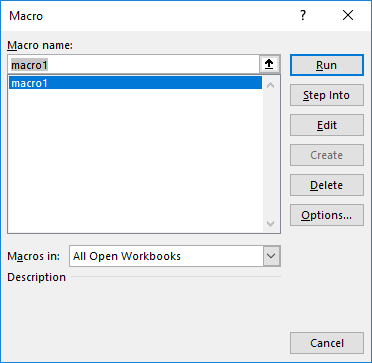

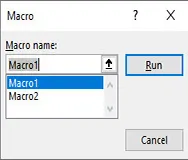

To run a macro, navigate to the Developer Ribbon and select Macros:

Then select your desired Macro and click Run:

Notice from this menu you can also select "Edit". Edit will open the code for that macro within the Visual Basic Editor.

AutoMacro is a VBA add-in that makes coding easier for everyone:

Simply select a code fragment from the AutoMacro menus and it will insert directly into the active module. AutoMacro contains finished procedures, and also smaller code fragments, allowing anyone to code VBA procedures from scratch. AutoMacro also contains many time saving features designed with experienced coders in mind.

If you find this site useful, please upvote us on Quora.

This lesson will introduce you to the basics of how VBA interacts with Excel. Learn how to use VBA to work with ranges, sheets, and workbooks.

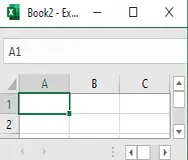

When working with VBA, you need to create procedures to store your code. The most basic type of procedure is called a "Sub". To create a new sub procedure, open the VBE and type Sub HelloWorld and press enter.

Sub HelloWorld()

End Sub

You have now created a sub titled "HelloWorld".

You will notice that the VBE completes the setup of the sub for you automatically by adding the line End Sub. All of your code should go in between the start and the end of the procedure.

You can add comments anywhere in your code by proceeding the comment with an apostrophe (') 'This is a Comment

Comments can be placed on their own line or at the end of a line of code:

row = 5 ‘Start at Row 5

Sub HelloWorld()

End Sub

Comments make your code much easier to follow. We recommend developing the habit of creating section headers to identify what each piece of code does.

You can program VBA to do anything within Excel by referencing the appropriate objects, properties, and methods.

Objects are items like workbooks, worksheets, cells, shapes, textboxes, or comments. Objects have properties (ex. values, formats, settings) that you can change. Methods are actions that can be applied to objects (ex. copy, delete, paste, clear). Let's look at an example:

Range("A1").Font.Size = 11

Sheets(1).Delete

In the example above:

Objects: Range("A1") , Sheets(1)

Properties: Font.Size

Methods: Delete

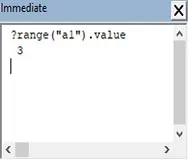

Now we will practice assigning properties to the range object. To assign the value of 1 to cell A1 you would type range("a1").value = 1 .

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Note: In the examples above, no sheet name was specified. If no sheet name is specified, VBA will assume you are referring to the worksheet currently "active" in VBA. We will learn more about this later.

When assigning numerical values to cells, simply type the number. However when assigning a string of text to a cell, you must surround the text with quotations.

Why? Without the quotations VBA thinks you are entering a variable. We will learn about variables in the next chapter.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

There are two more important details to keep in mind as you work with strings. First, using a set of quotations that doesn't contain anything will generate a "blank" value.

range("a3").value = ""

Second, you can use the & operator to combine strings of text:

"string of" & "text"

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Anything in VBA that's surrounded by quotations is considered a string of text. Remember that when you enter a range, sheet name, or workbook you put the range in quotations (ex "A1"), which is just a string of text. Instead of explicitly writing the string of text you can use variable(s).

Dim strRng

strRng = "A1"

range(strRng).value = 1

is the same as

range("a1").value = 1

Here we've declared a variable strRng and set it equal to "A1". Then instead of typing "A1", we reference the variable strRng in the range object.

Now you try.

Sub Macro1()

Dim Row

Row = 5

End Sub

We will learn more about variables in a future lesson.

Named Ranges are cells that have been assigned a custom name. To reference a named range, instead of typing the cell reference (ex. "A1"), type the range name (ex "drate").

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Named ranges are very useful when working in Excel, but they are absolutely essential to use when working with VBA. Why? If you add (or delete) rows & columns all of your Excel formulas will update automatically, but your VBA code will remain unchanged. If you've hard-coded a reference to a specific range in VBA, it may no longer be correct. The only protection against this is to name your ranges.

Now instead of assigning a value to a single cell, let's assign a value to a range of cells with one line of code.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

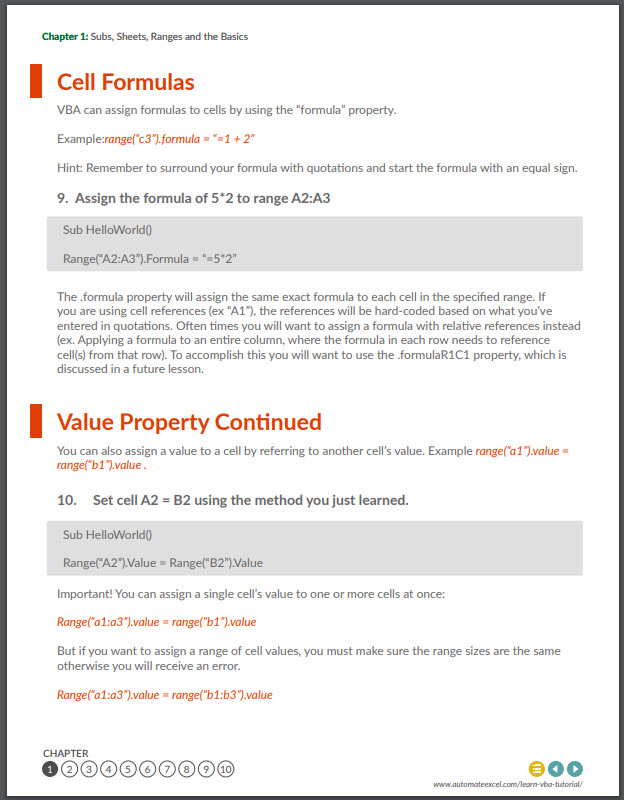

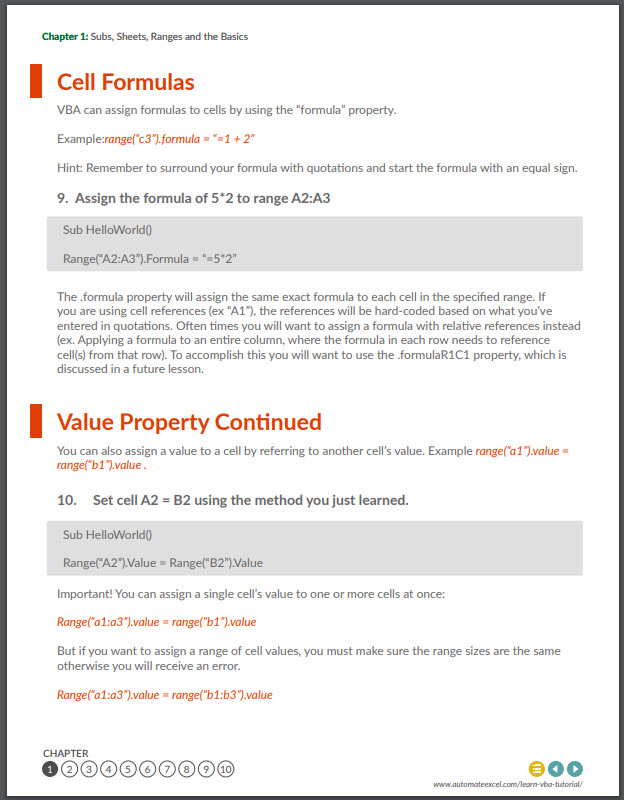

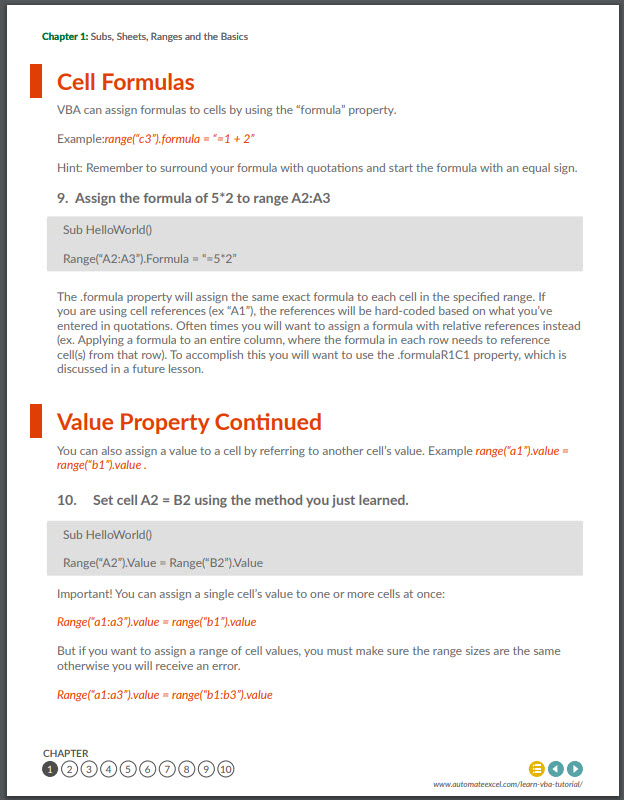

VBA can assign formulas to cells by using the "formula" property.

Example:range("c3").formula = "=1 + 2"

Hint: Remember to surround your formula with quotations and start the formula with an equal sign.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The .formula property will assign the same exact formula to each cell in the specified range. If you are using cell references (ex "A1"), the references will be hard-coded based on what you've entered in quotations. Often times you will want to assign a formula with relative references instead (ex. Applying a formula to an entire column, where the formula in each row needs to reference cell(s) from that row). To accomplish this you will want to use the .formulaR1C1 property, which is discussed in a future lesson.

You can also assign a value to a cell by referring to another cell's value. Example range("a1").value = range("b1").value .

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Important! You can assign a single cell's value to one or more cells at once:

Range("a1:a3").value = range("b1").value

But if you want to assign a range of cell values, you must make sure the range sizes are the same otherwise you will receive an error.

Range("a1:a3").value = range("b1:b3").value

There are also many methods that can be applied to ranges. Think of methods as "actions". Examples of methods include: .clear, .delete, and .copy. Try applying the .clear method. This will clear all of the cell's properties (values, formulas, formats, comments, etc.)

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Now use the .clearcontents method to only clear the cell's contents, keeping the cell's formatting and all other properties. This is the equivalent of pressing the Delete key.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

When you refer to a range without explicitly declaring a worksheet or workbook, VBA will work with whichever worksheet or workbook is currently active in the procedure. Instead you can (and should) explicitly tell VBA which worksheets and workbooks (if applicable) to use. See the examples below.

No WS or WB, will use whatever is active.

range("a1").value = 1

No WB, will use whatever is active, but a WS is declared. This is fine if your procedures won't reference other workbooks.

Sheets("Inputs").range("a1").value = 1

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Both WB and WS are defined.

Workbooks("wb1.xlsm").sheets("inputs").range("a1").value = 1

Notice that when defining a workbook you must add the appropriate file extension (.xls, xlsm, etc.).

Try for yourself:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

As you may have noticed, it's quite a lot of typing to define worksheets and workbooks. Imagine typing that over and over again… Instead you should utilize worksheet and workbook variables to simplify your code. We will cover this in the chapter on variables.

If you've ever recorded a macro, you've probably seen .Activate and .Select used to activate or select an object (ex. A range). These commands effectively shift the focus to the desired object(s):

range("a1").select

Selection.value = 1

The above code is identical to this:

range("a1").value = 1

The second instance is much shorter, easier to follow, and less error prone. In fact, you should almost never use .activate or .select. You can almost always accomplish the same task by writing smarter code. If you are editing code from a recorded macro, you should consider "cleansing" your code of .activate and .selects.

The only time you should use these commands is when shifting the focus for the user.For example, you might want to add a navigation button to jump to a different worksheet:

Sub nav_Index()

Sheets("index").activate

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

What's the difference between activate and select? Only one object of the same type can be active at a time (ex. activesheet, activeworkbook, activecell, etc.) whereas multiple objects of the same type can be selected at once (a range of cells, multiple shapes, multiple worksheets, etc.).

There are numerous objects, properties, and methods that you can access with VBA. It's impossible to cover them all in a tutorial. Luckily, All of them operate using the same principles and syntax.

Variables are like memory boxes that you use to store objects (e.g. workbooks or worksheets) or values (e.g. integers, text, true/false). When you set up a variable, it can easily be changed in VBA by performing some calculation with it.

There are many different types of variables, but there are two main categories:

Declaring a variable tells VBA what kind of information the variable will store. You can declare different number types, strings (to store text), objects (worksheets, workbooks), dates, and much more.

To declare a string variable:

Dim StringVariable as string

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

To declare other variable types use the same syntax except replace "string" with "long" (for integer numbers), "variant", "date" or whatever other variable type you want to use.

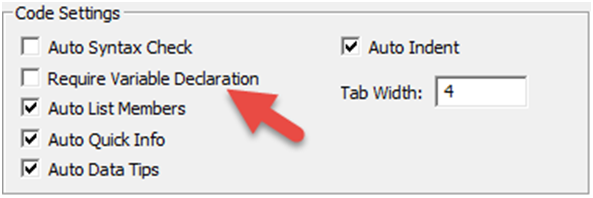

Here's the thing about declaring variables… You don't actually need to do it,unless you enter Option Explicit at the top of your module or you change your VBA options to require it:

That being said, any serious programmer will tell you that you should always use Option Explicit and declare your variables. Declaring variables helps prevent coding errors (ex. If you misspelled a variable or if you use the same variable across multiple procedures), but doing so increases the VBA learning curve. The choice is up to you.

Even though you don't necessarily need to declare your variable type before using them, you need to understand the variable types. See the chart below and we will practice variables in the next section.

| Grouping | Variable type | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical | Integer | Accepts only integer values, mainly used for counters; value needs to be between -32768 and 32767. Note: You should always use Long instead of Integer. Integer numbers used to be needed to reduce memory usage. But it is no longer necessary. |

| Numerical | Long | Accepts only integer values, used for larger referencing like populations; value needs to be between -2,147,483,648 and 2,147,483,648 |

| Numerical | Double | Accepts decimal values with significant degree of precision; values need to be between -1.79769313486231e308and -4.94065645841247e-324 for negative numbers and 1.79769313486231e308and 4.94065645841247e-324 for positive numbers. |

| Text | String | Accepts strings of text, usually identified with double quotation marks; if a value is input without quotation marks, it will be automatically recognised as text. |

| Date/Time | Date | Accepts dates, needs to be between # signs, e.g. #31/12/1999# |

| Boolean | Boolean | Accepts True or False values. |

| Any | Variant | Accepts any type of variable. |

| Objects | Workbook | Accepts workbook names. |

| Objects | Worksheet | Accepts worksheet names. |

| Objects | Object | Accepts all objects |

Declare variables like this

Dim i as long

i = 1

Dim j as Double

j=1.1

Remember use "Long" for integer numbers and "Double" for decimal numbers. You try:

Sub Macro1()

Dim j as long

End Sub

Once you assign a value to a variable it's easy to change that value. With number variables you can even perform operations to recalculate the variable.

Sub Macro1()

Dim j as long

j = 2

End Sub

Use variable j to assign a value to a cell:

Sub Macro1()

Dim j as long

j = 2

j = j + 1

End Sub

Now let's practice declaring different numerical variables:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can also store non-numerical values in variables. Let's practice with the string variable type:

Sub Macro1()

Dim strTest as string

End Sub

Still working with string variables, assign a cell value to a variable

The cell value will now be stored as text, regardless of whether the cell value is a number or text.

Sub Macro1()

Dim strTest as string

End Sub

Unless you're a programmer, you probably haven't heard of Boolean variables. A Boolean variable can only have two possible values: TRUE or FALSE. TRUE / FALSE is not treated as text, but instead as a logical value (similar to how Excel treats TRUE / FALSE). When using Boolean variables, don't surround TRUE / FALSE with quotations

Sub Macro1()

Dim Flag as Boolean

End Sub

What if you want to switch the TRUE / FALSE indicator? Use the Not command: Flag = Not Flag

Sub Macro1()

Dim Flag as Boolean

End Sub

Object variables can store objects (workbooks, worksheets, ranges, etc.). You declare object variables in the same way you would declare any other variable. However, the process to assign an object to a variable is slightly different; you must add "Set"to the assignment.

Dim myWB as Workbook

Set myWB = Workbooks("Example.xlsm")

The same can be done to define a worksheet as a variable:

Dim myWS as Worksheet

Set myWS = Workbooks("Example.xlsm").Sheets("Inputs")

But why would you want to use a variable to store a worksheet or workbook if you can just reference the worksheet or workbook? Imagine doing multiple calculations on the same workbook and needing to reference it everytime:

Workbooks("Example.xlsm").Sheets("MySheet").Range("A1").Value = 4

Workbooks("Example.xlsm").Sheets("MySheet").Range("A2").Value =51

Workbooks("Example.xlsm").Sheets("MySheet").Range("A3").Value =26

This can easily be simplified to the following:

Dim myWS as Worksheet

Set myWS = Workbooks("Example.xlsm").Sheets("MySheet")

myWS.Range("A1").Value = 4

myWS.Range("A2").Value = 51

myWS.Range("A3").Value = 26

Much easier when you reference the same sheet over and over again!

Now you try :

Sub Macro1()

Dim myWB as Workbook

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

Dim myWS as Worksheet

End Sub

We've mentioned several times that if you don't explicitly indicate a specific worksheet, the active sheet is used (the same goes for workbooks). VBA keeps track of the active sheet and allows you to reference it via the "activesheet", which is essentially a variable that VBA updates as needed. VBA does the same with the active workbook, the active cell, and actually allows you the ability to reference the workbook where the code is stored (not necessarily the activeworkbook).

Msgbox activesheet.name ‘Name of active sheet

Msgbox activeworkbook.name ‘Name of active workbook

Msgbox activecell.name ‘Name of active cell

Msgbox thisworkbook.name ‘Name of workbook where this code is stored

You can use these just like any other variables. Often though, you'll want to assign the activesheet and/or activeworkbook to other variables to use later when the active sheet or workbook changes. Ex:

Dim myWB as Workbook

Set myWB = ActiveWorkbook

Sub Macro1()

Dim curWB as Workbook

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

Dim myWS as Worksheet

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You might be wondering how the active workbook or worksheet changes. What is considered "active"?

When you first run a procedure, the active sheet (workbook) is the sheet (workbook) that is currently visible . The active workbook will only change if

workbooks("wb2.xlsm").activate Or workbooks("wb2.xlsm").select

The active sheet will only change if

sheets("newWS").activate Or sheets("newWS").select

We cover this in more detail in a future lesson, but you should almost NEVER change the active worksheet or workbook. You should only do so to change what sheet (or workbook) the user will see once your code has finished running.

Remember earlier we said that anything in quotations in VBA is just a string and that you can create range references from strings of text? Of course you can do the same thing with worksheets and workbooks.

Sub Macro1()

Dim strWS as String

End Sub

Now if one of your sheets is called "2017_12" it you can easily reference that sheet by doing the following:

Sheets(strWS).Range("A1").Value = 2

This is useful if you want to reference a worksheet name based on some inputs:

strWS = Year(Now & "_" & Month(Now)

Sheets(strWS).Range("A1").Value = 2

Sub Macro1()

Dim strWS As String

End Sub

Logical tests allow you test if conditions are met, doing one thing if the condition is met, or another if it is not.

Before continuing, you must understand some basic operators:

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| = | Equal to |

| <> | Not Equal to |

| < | Less than |

| > | Greater than |

| <= | Less than or equal to |

| >= | Greater than or equal to |

These operators compare values, returning the Boolean values: TRUE or FALSE.

test = 5 > 3

Returns TRUE

test = 5 >= 3

Returns TRUE

test = 5 <> 5

Returns FALSE

Sub Macro1()

Dim Test as Boolean

End Sub

The "=" and "<>" operators can also be used to compare text

test = "String" = "Text"

Returns FALSE

test = "String" = "string"

Returns FALSE – By Default, VBA actually treats upper and lower case letters as different text. To ignore case when comparing values you must add "Option Compare Text" at the top of your module.

Option Compare Text

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Remember variables? You can compare variables as well:

Option Compare Text

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

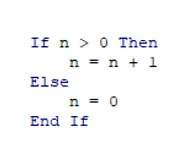

Using the "IF" statement, you can use those same logical operators to test whether a statement is TRUE or FALSE and perform one action if TRUE and another action if FALSE. If you're familiar with the Excel IF Function then you know how this works.

If n < 0 then

Data_val = "Warning! Negative Value"

Else

Data_val = "ok"

End if

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can test multiple conditions with a single "IF" statement by using the "And" and "Or" operators.

To test whether a number n is between (but not equal) to 3 and 10, you will use the "And" indicator.

If (n > 3) and (n < 10) then

Range("A1").Value = "in range"

End if

Notice that you don't need to add the line "Else" if you don't need to run anything if the condition is FALSE. In fact you could write the code in one line and you can omit "End IF":

If (n > 3) and (n < 10) then Range("A1").Value = "in range"

For short IF statements, this may be the "cleanest" way to write an IF statement. Now back to more exercises.

Use the operators ">=" and "<=" to test if a number is "greater than or equal to" or "less than or equal to".

Sub Macro1()

'do something

End If

End Sub

Use "Elseif" to test a second condition if the first is false:

If animal = "Cat" then

MsgBox "Meow"

ElseIf animal = "Dog" then

MsgBox "Woof"

Else

MsgBox "*Crickets*"

End if

Sub Macro1()

If animal = "cat" Then

MsgBox "Meow"

ElseIf animal = "Dog" Then

MsgBox "Woof"

Else

MsgBox "*Crickets*"

End If

End Sub

You can embed one if statement inside another. For example, let's say we want to test whether the number n is greater than 3. If TRUE, we want to test whether the number m is greater than 3.

If n > 3 then

If m > 3 then

Range("A1").Value = "n greater than 3 and m greater than 3"

Else

Range("A1").Value = "n greater than 3 but m less than or equal to 3"

End if

Else

Range("A1").Value = "n less than or equal to 3 and we don't know about m"

End if

Select Case is an efficient way to do multiple logic tests in VBA. First you indicate a variable, object or a property of an object that you wish to test. Next you define "cases" that test if the variable, etc. matches and if so, do something.

To test a specific value (that is whether the variable is equal to a value), we can simple type the value after the word Case. If we want to use an operator to test a value, we have to type the word "Is" before we enter the operator.

Select Case i

Case Is <= 2: MsgBox "i is less than or equal to 2"

Case 3: MsgBox "i is equal to 3"

Case 4: MsgBox "i is equal to 4"

End Select

Here's an example using a cell.value instead:

Select Case cell.value

Case Is <= 2: MsgBox "i is less than or equal to 2"

Case 3: MsgBox "i is equal to 3"

Case 4: MsgBox "i is equal to 4"

End Select

Now you try:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Loops allow you to "loop" through a set of code multiple times. You can define a set number of instances for the loop to run, run until a condition is met, or loop through all the objects of a certain type. Loops are massive time-savers.

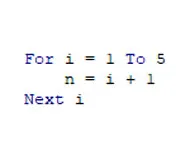

For loops repeat a block of code a set number of times either by running through a set of numbers, or through a defined series of objects. We will review some examples:

This first example defines a set number of times to repeat a task:

Dim i as long

‘Repeat tasks 10 times

For i = 1 to 10

‘perform tasks here

Next i

This next example, starts at i=1 and cycles through 10 times, each time increasing i by 1 (ex. i = 1, i =2, etc.). "i" is a variable and can be used like any other variable:

Dim i as long

‘Repeat tasks 10 times

For i = 1 to 10

Range("a" & i).value = 5 * i

Next i

After the loop, the variable stays at its most recent value (i = 10) and can be used as usual.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can change the direction and magnitude of the "steps":

Dim i as long

For i = 10 to 0 step -2

'Do Something

Next i

This loop starts at i = 10 and goes to 0, decreasing by 2 each time. With the "step" feature you can define the intervals for the loop, which can be positive or negative.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

For Each loops allow you to cycle through all the objects in a group such as cells in a range or all worksheets in a workbook.

To loop through each worksheet in the workbook:

Dim ws as worksheet

‘Repeat tasks on each worksheet

For each ws in worksheets

Ws.unprotect

Ws.range("a1").value = ws.name

Next ws

Loop through each cell in a range:

Dim cell as range

For each cell in range("a1:a1000")

Cell.value = cell.offset(0,1).value

Next Cell

In the above examples "ws" and "cell" are both object variables. Within the loop, you can simply write "ws." Or "cell." followed by the property or method that you wish to apply on each worksheet or cell.

Sub Macro1()

Dim ws as Worksheet

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

Dim cell as Range

End Sub

Do While and Do Until loops allow you to repeat some code while a condition is met or until a condition is met. You need to be careful with these type of loops. If the condition never changes, the loop will run continuously and you will need to restart Excel. These loops look like this:

Do

‘Perform tasks here

Loop until range("a1").value > 5

Here we are looping until a certain condition is met. By placing the "until..." at the end we tell VBA to run the code first before checking to see if the condition is met or not. Alternatively, you can place the "until..." at the beginning and then VBA will check the condition before running the code:

Do until range("a1").value > 5

‘Perform tasks here

Loop

Instead of looping "until" a condition is met, you can loop while a condition is met, stopping once it's no longer met:

Do while range("a1").value <= 5

‘˜Perform tasks here

Loop

Again, "while" can go at the beginning or the end:

Do

‘˜Perform tasks here

Loop while range("a1").value <= 5

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

As you can see, loops are absolutely essential to automating tedious repetitive processes!

In the first chapter we discussed the basics of using VBA to interact with cells, sheets, and workbooks. In this chapter we learn more advanced techniques and also discuss how to interact with rows, columns, and more.

Let's work through some examples regarding rows and columns in VBA.

To get the row number of a cell:

row_num = range("a3").row

This isn't particularly useful if you hard-code the range "A3" (you already know the row number). Instead, practice with a named range:

Sub Macro1()

Dim row_num as Long

End Sub

Now use .column to get the column number.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You already know about the Range, Worksheet, and Workbook objects. You might also find the Rows and Columns objects useful.

This code snippet will delete rows 2 & 3

Rows("2:3").delete

Your turn:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can also insert rows and columns:

Columns("H").insert

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Alternatively, you can refer to entire columns and rows by adding ".EntireColumn" or ".EntireRow" after referring to a Range.

range("b3").EntireColumn.insert

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Rows and Columns have a property called "hidden" that is set to TRUE or FALSE. To hide a row:

rows("a").hidden = true

Or

range("a1").entirerow.hidden = true

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The .Count method is used to count the number of cells in a range.

n = range("data").count

Sub Macro1()

Dim n as Long

End Sub

To copy range "A1" and paste into range "B1":

Range("A1").Copy Range("B1")

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

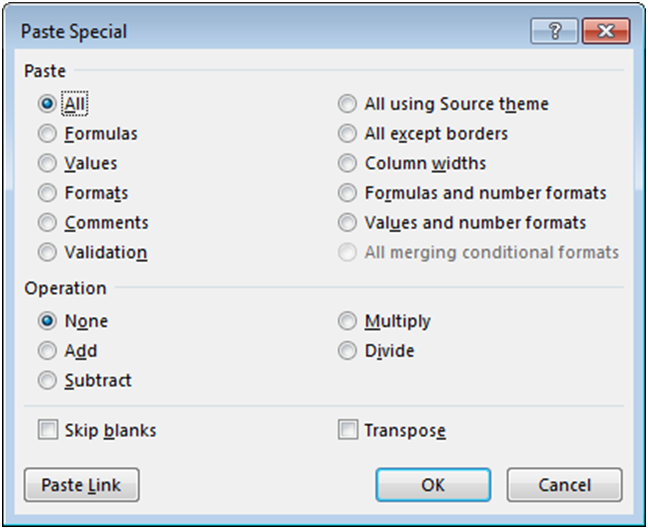

Paste Special allows you to paste only certain properties of the cell, instead of all cell properties (ex. only cell values). With Paste Special you must use two lines of code:

Range("A1").Copy

Range("A2").PasteSpecial Paste:=xlPasteFormats

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can also use xlPasteValues , xlPasteFormulas, or any of the options available to you in the Paste Special Menu:

Earlier we introduced you to how to reference cells in Excel using the Range object. With the Range object we taught you to reference cells by referring to their column letter and row number. This is called A1-style cell-referencing. Instead you can use R1C1-style referencing, where you can refer to the column number instead of its letter. This is very useful as we will see below. Example:

range("R3C2") refers to cell "B3". To use R1C1-style referencing type "R" followed by the row number and "C" followed by the column number.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The Cells Object provides you another option for referring to cells using column and row numbers. When using the cells object, first enter the row number then enter the column number. Example:

cells(3,2) refers to cell "B3".

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

One frequent problem when working with VBA is defining the appropriate ranges for your work. For example, you have several columns of data, and you wish to add an additional column of calculations. What column should you place your calculations in? How far down should your calculations go (which row)? Luckily, VBA provides us with several useful commands to help us out.

Excel keeps a record of the last used cell in each worksheet called the Used Range. The Used Range helps keep the file size and calculation time as small as possible by telling Excel to ignore all cells outside of the Used Range. You can reference the Used Range in VBA to find the last used cell.

lrow = Activesheet.UsedRange.row

This code finds the last used row in the Activesheet and assigns it to variable "lrow"

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Unfortunately, you need to be careful relying on the Used Range. It won't always provide the answer that you expect. A couple things to keep in mind:

UsedRange finds the last used cell in the entire worksheet. Instead, you may want to find the last used cell in a row or a column. You will need to use the ".End" method:

range("a3").End(xlDown).Row

This is the equivalent of pressing CTRL + Down Arrow while in cell "A3". If you aren't familiar with the CTRL + Arrow shortcut, you should really learn it. It's a massive Excel time-saver. CTRL + Arrow jumps to the last non-blank cell in a series, or the first non-blank cell after a series of blank cells.

The above example will find the last used cell in column A, but only if there aren't any blank cells in column A (Before the last used cell). To be safe, you must start your .End at the bottom of the worksheet and work your way up. You can define a range to start with:

range("a1000000").End(xlUp).row

Or you can use this more complicated code:

With ActiveSheet

LastRow = .Cells(.Rows.Count, "A").End(xlUp).Row

End With

Notice here that Rows.Count counts the number of rows in the worksheet.

You can do the same with columns, however the syntax is a little different. Instead of "xlLeft", you use "xlToLeft" and "xlToRight".

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Offset allows you to offset a cell range by a number of rows or columns

range("a1").offset(2,1).select

This will select cell B3 (2 down, and 1 to the right of cell "A1").

You might find Offset useful when cycling through ranges of cells

For each cell in range("a1:b3")

Cell.value = n

Cell.offset(0,1).value = n + 1

Cell.offset(0,2).value = n + 2

Next cell

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Resize allows you to resize a range of cells to a specific number of rows and columns. It works very similarily to Offset. It's important to keep in mind that resizing specifies the total number of rows and columns in the new range not the number of rows and columns to add (or subtract) to the existing range. Resize(0,0) will result in an error. To resize to a single cell use Resize(1,1). Also, keep in mind that your starting cell, will always be the upper-leftmost cell in the range.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You can even use Resize and Offset in the same line of code:

range("a1").offset(1,1).resize(2,2).select

In the first chapter, you were introduced to the formula property where you could assign a formula to a cell:

range("a1:a10").formula = "=b1"

Another formula option is the FormulaR1C1 property. The following code will generate an identical result to the code above:

range("a1:a10").formulaR1C1 = "=R1C2"

Cell "B1" is row 1 of column 2 (R1C2).

Try for yourself:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

When you use either of these techniques, your formula is "hard-coded", meaning the formula will be applied exactly the same to the entire range of cells. In the first example above, all cells "A1" to "A10" will have the formula "=b1".

Instead, often you will want to use "relative references" with the formulaR1C1 property R[1]C[1]. With relative references your formula references are proportional to each specific cell. They are not "hard-coded". So when applying a formula down a column cell A1 = B1, cell A2 = B2, cell A3 = B3, etc.:

range("a1:a10").formular1c1 = "=RC[1]"

In this example, the "[1]" after "C" indicates the first column to the right of the cell containing the formula. The brackets indicate "relative" references. When using relative references, you indicate how many rows/columns to offset from the current cell. By not having anything after "R", you are telling VBA to look at the same row. If you use numbers without brackets, you are using the regular R1C1 cell references that we learned about before. Those references are hard-coded, and will not move.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

You will probably use R[1]C[1]-style referencing the most when working with cell formulas in VBA. This technique can be hard to remember and it is very easy to make mistakes. We recommend recording a macro, entering the formula directly into Excel, and then copying/pasting that recorded formula into your main procedure.

Activecell references the currently active cell within VBA.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

So far we've mostly used the Sheets object to identify which sheet to work with. Now we will learn about the worksheet methods and properties.

To hide a sheet:

sheets("data").visible = false

Now try unhiding a sheet using the same method:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The Visible property actually has a third option: xlSheetVeryHidden. In addition to hiding the worksheet tab, the tab can't be unhidden from within Excel. It will disappear from the sheets list, and can only be unhidden using VBA.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

It's easy to change a worksheet name:

sheets("data").name = "data_old"

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Worksheets can be password protected to prevent a user from accidently corrupting the workbook. If you password protect a worksheet, you will need your code to unprotect the worksheet before it can make changes to any protected properties, and re-protect the sheet once the code finishes running.

To protect a worksheet:

sheets("calcs").protect "password"

Instead of "password", enter the actual password, or you can actually ignore the password argument if you want to protect the sheet, but don't want to require a password to un-protect it.

To unprotect a worksheet, use the same syntax.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The Protect method actually has many other arguments indicating what a user can and cannot do to the worksheet. The best way to get the options that you want is to Record a Macro with the appropriate settings and then copy&paste the recorded code into your procedure.

Message boxes and Input boxes are used to communicate information to the user or receive information from the user.

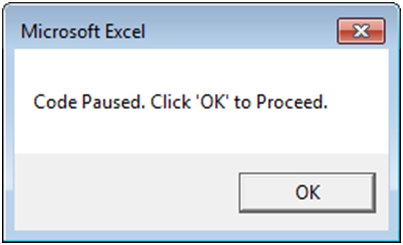

Message boxes allow you to communicate information to the user, while pausing the code until feedback is provided by the user. This is the most basic message box form:

msgbox "Code Paused. Click ‘OK' to Proceed."

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

These type of message boxes are called vbOKOnly. They only have one option for user interaction (clicking the "OK" button), but there are many other message box types with different interaction options. The general syntax for MsgBox is

MsgBox(prompt[, buttons] [, title] [, helpfile, context])

Where anything in brackets ([]) is optional. If the optional arguments are left blank, then they are set to the default values. For example, if you leave "buttons" blank, it will default to the simple vbOKonly (as in our example above).

Now let's try including the button type, and title. Example:

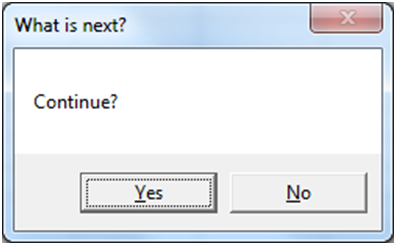

vInput = MsgBox("Continue?", vbYesNo, "What is next?")

When this statement is executed, you will see the following message box appear:

This is a vbYesNo message box. When "yes" or "no" is clicked, the message box will output vbYes or vbNo to a variable (vInput in our example). vbYes can also be used as the integer value 6 and vbNo as 7.

Now we will use an If statement to do something depending on what the answer is:

vInput = MsgBox("Continue?", vbYesNo, "What is next?")

If vInput = vbYes Then

msgbox "You selected Yes"

Else

msgbox "You selected No"

End If

If the user selects "Yes" then vInput is set to vbYes and the message box "You selected Yes" is displayed.

Your turn:

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

The great thing about message boxes, is that you can ask the user in the middle of the code, what actions they want to take. It's a little like a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure novel.

vbOKOnly, vbYesNo, and vbYesNoCancel are the most commonly used message box types. There are many other types. We've listed a few below:

The InputBox is similar to the MsgBox, except the InputBox allows the user to input information. Let's look at the most basic form of the InputBox:

Dim myValue as Variant

myValue = InputBox("What is your name?")

msgbox myValue

The variable myValue receives the user input from the InputBox.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Now let's add a title and a default value to the InputBox. The default value will pre-populate in the input area.

myValue = InputBox("What is your name?","Hello","John Doe")

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Below we've included the general syntax for InputBox:

InputBox(prompt[, title] [, default] [, xpos] [, ypos] [, helpfile, context])

MsgBox and InputBox work well to take very basic input from the user. However, to create fully customized forms you need to use UserForms. UserForms allow you to add buttons, checkboxes, togglebuttons, text, inputforms, images, scrollbars, and more. You can trigger procedures to run when certain "events" happen, like selecting an option. UserForms are built from scratch within the VBE.

Unfortunately, because UserForms are so flexible, they often require quite a bit of coding to set up.

Many of you will never need to design UserForms, so we won't include them here in detail. Instead, when you do work with them, we recommend searching online for guidance.

An event is an action that can trigger other code to run. Examples of events include changes to a specific worksheet, activating a worksheet, opening a workbook, saving, and closing.

An event is an action that can trigger other code to run. Examples include: any cell in a worksheet is changed, a worksheet is activated, before saving a workbook, or before closing a workbook.

As of writing this, there are over 100 different events that can trigger event procedures. Events can be categorized into five categories:

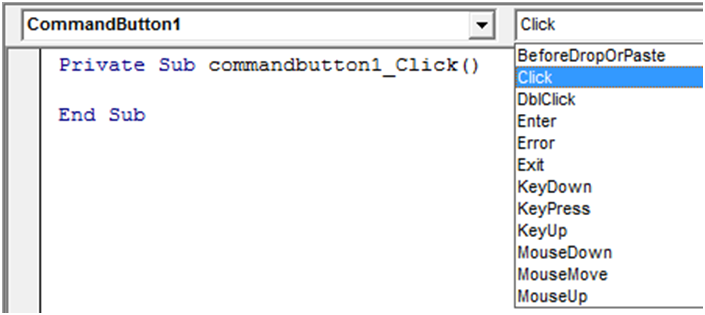

We ended the previous chapter with an introduction to Userforms, so we thought we'd pick up where we left off with one Userform event example. To run code when a Userform button is clicked place the following code in the Userform module within VBA:

Private Sub CommandButton1_Click ()

‘˜Do Something

End Sub

Where "CommandButton1" is the name of the button.

If you don't remember the exact syntax for an event or you want to see a list of events available to you, navigate to the top of the code window and 1. select the appropriate object (userform, userform items, worksheet, or workbook) and 2. activate the second drop down to see your options:

Private Sub CloseButton_Click()

End Sub

You can see a list of relevant events by first selecting the appropriate Userform object from the drop down on the left (at the top of your code window) and then activating the drop down on the right:

You can see there are quite a few events, that allow you to create fancy user interfaces.

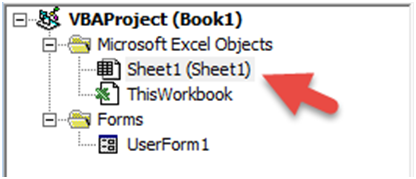

Worksheet-level events include: changes to a worksheet, activating a worksheet, deactivating a worksheet, and more. To create a worksheet-level event, you will need to place your code in the appropriate worksheet module:

One of the most popular worksheet-level events is the worksheet_change event. The worksheet change event will run whenever there is a change to the worksheet.

Private Sub Worksheet_Change(Byval Target as Range)

Msgbox Target.row

End Sub

Notice that we need to declare the variable "Target" as a range, allowing it to be passed into the event procedure so that you can refer back to the changed range within the procedure. Be careful! Your range could be more than one cell, so you will need to build your code accordingly.

You may be wondering what "Byval" means. "Byval" means the variable is locked in as a value and cannot be changed within the procedure.

Private Sub Worksheet_Change(Byval Target as Range)

End Sub

Workbook-level events, must be placed in the ‘ThisWorkbook' module:

Workbook-level events are triggered for things like saving, opening, closing the workbook where the code is contained.

Private Sub Workbook_BeforeClose(Cancel as Boolean)

Msgbox "Closing…"

End Sub

Application-level events can be placed wherever.

Application-level events are triggered when ANY workbook is opened, closed, saved, created, etc. Often, application-level events will pass along the workbook as a workbook variable, allowing you to easily refer to it. See this in the example below:

‘˜Add a New Sheet on WorkbookOpen

Private Sub App_WorkbookOpen(ByVal Wb As Workbook)

Wb.sheets.add

End Sub

This code will add a worksheet to any workbook that is opened.

We can't cover all the events available to you. Instead, if you think you might want to add an event to your workbook, do a quick online search.

In this chapter we will introduce you to settings that will speed up your code and improve the user experience. You should use these VBA commands over and over again in all of your procedures.

Notice how your screen flickers when a procedure runs? Excel is trying to update the display based on the code running. This slows down your code substantially. You can disable it by adding this to the top of your procedure:

application.screenupdating = false

Then at the end of your procedure, re-enable it:

Sub Macro1()

Application.ScreenUpdating = False

End Sub

Disabling screen updating also makes your code look much more professional. This is a must use setting.

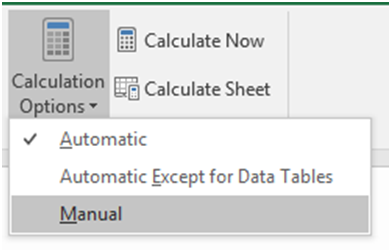

You may already know that you can disable Automatic Calculation within Excel:

This stops Excel from calculating your workbook until you re-enable calculations or until you tell Excel to calculate. Disabling auto calculations can make a huge difference in processing speed.

Add this to the beginning of your procedure:

Application.Calculation = xlManual

And make sure to re-enable auto calculations at the end of your procedure:

Sub Macro1()

Application.Calculation = xlManual

End Sub

Of course you need to be careful that you aren't relying on calculated values from within your code with calculations turned off. If you do, you'll want to manually calculate the workbook with this simple command:

Calculate

You can also calculate specific sheets or ranges by applying the .calculate method.

Sub Macro1()

Application.Calculation = xlManual

End Sub

The StatusBar is in the lower left-hand corner of Excel

You can disable the status bar so that it doesn't update while running code:

application.displaystatusbar = false

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

This will only slightly improve processing speed.

More useful though is the ability to set custom StatusBar messages:

application.statusbar = "Custom Message"

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Earlier we introduced you to Events that you can use to trigger code (Event Procedures) to run. These events can be great for the end-user, but while developing the workbook, you probably want to disable them. Also, within your procedures you may need to disable events to avoid an endless loop. For example, if you have a worksheet_change event that makes changes to that same worksheet, your code will result in an endless loop. You will need to disable events to avoid this.

To disable events:

application.enableevents = false

Sub Macro1()

Application.EnableEvents = False

End Sub

You can pause code by pressing the ESC key or CTRL + Pause Break. You, as a developer wants this ability, however, this is a prime opportunity for your users to screw something up. Don't risk it. Instead disable the cancel key at the beginning of your code:

Application.EnableCancelKey = xlDisabled

By setting it to xlInterrupt you can turn the cancel key back on again.

Sub Macro1()

Application.EnableCancelKey = xlDisabled

End Sub

When you first start coding, you will probably create a single sub procedure that completes your desired task from start to finish. As you become more sophisticated, your code will be split across multiple procedures in different modules.

This section covers the different options available to you as your code becomes more complex.

You can call a sub procedure from within another sub procedure:

Sub Macro1 ()

Call Macro2

End Sub

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Earlier we talked about declaring variables within a procedure. A variable declared within a procedure can't be used outside of that procedure. If you need to use the same variable in multiple procedures, you have two options. First, you can declare a Public variable by placing code like this at the top of a module:

Public variable_name as string

Where "variable_name" is the name of the variable you wish to declare. Of course you can declare any type of variable: string, long, etc.

By declaring a Public Variable, you can use the variable in as many functions, or procedures as you'd like. The variable value will be stored in memory, so if you assign a value to that variable in one procedure, that value can be accessed in other procedures.

Public m as long

Global and Public variables behave virtually identically. Global is a declaration used in earlier versions of Visual Basic and has been kept for backwards compatibility. The Global declaration won't work in certain cases, whereas the Public declaration will always work. With that in mind, we recommend using Public variables.

Global variable_name as string

As an alternative to using Public variables, you can pass variables from one procedure to another. In order to do so, first you need to prepare your procedure to accept variables:

sub Procedure2(n as long, str as string)

When declaring variables in this way, you do not need to add "dim" to the front of the declaration.

Now Procedure2 can accept an integer and a string as inputs when that procedure is called:

Sub Procedure1 ()

Call Procedure2 (23, "MJ")

End Sub

Sub convert (name as String, count as Long)

End Sub

Remember the "ByVal" declaration from earlier (sections on Userforms and Events)? The ByVal declaration locks in the variable value once it's passed to the procedure. You will not be able to change the variable value from within that procedure. Example:

sub Procedure2(ByVal n as long, ByVal str as string)

Use ByVal to prevent errors in situations where the variable value can not be changed

So far we've only dealt with Sub Procedures. Function Procedures are very similar to Subs with two main differences:

You create Functions just like creating Subs, except you should declare the function as a variable type (assuming you have option explicit enabled):

Function MaxValue (a as long, b as long) as long

Function GetCalc(a as Long) as Long

End Function

Let's look at an example where we want to calculate the maximum between two values.

Function MaxValue (a as long, b as long) as long

If a >= b Then

MaxValue = a

Else

MaxValue = b

End If

End Function

Here we've defined the function MaxValue. When we call this function, we need to specify two numbers, a and b. The function will then check if a is greater or equal to b; if it is, the function will return the value of a. If not, it will return the value of b.

Notice that to assign the result to the Function, you enter "Function Name = ….."

Calling a function is a bit different from calling a sub. Because your function will return a value, you will need to assign the function's value to something (often a variable). Let's look at how we will call our MaxValue function from a sub.

Sub Macro1 ()

TheMaximum = MaxValue(10,12)

End Sub

In this example, we will call the MaxValue function and check which of the values 10 or 12 is the maximum. Then the value of 12 will be returned and stored in the variable TheMaximum.

The great thing about functions are that they don't only work in the VBE. You can also call them directly from your worksheet! After you've created the function above in a new module in the VBE, go to you Excel worksheet and start by typing "=MaxValue". Do you see your newly created function?

Function MinValue (a as long, b as long) as long

If a > b Then

MinValue = b

Else

MinValue = a

End If

End Function

Earlier we introduced you to Public variables. These are variables that may be used anywhere. By default, all functions and procedures are also considered "public". Public Functions can even be used in an Excel workbook similar to Excel's default functions.

Private variables, functions, and subs can only be used within the module where they reside. They can't be called by the user from the OPEN MACROS dialog box. To declare a private (module-level) variable, make a declaration at the top of your module, similar to declaring a public (global) variable:

Private n as long

Private str as String

To make a sub or function Private just add "Private" to the beginning of your procedure declaration:

Private Function TestFx (str) as string

Private Sub TestSub()

End Sub

You can also make an entire module private by adding this to the top of your module:

Option Private Module

Try it for yourself:

Option Private Module

In broad programming terms, an Array is a series of objects of the same type. Usually arrays are used to store sets of data. Think of arrays in a similar way to a series of cells in an Excel worksheet. You can return values in an array by referencing its position in the array, similar to how you can reference a cell based on its column and row numbers.

Arrays are at the core of every programming language, but when working with Excel, arrays aren't necessary because you can store information within ranges of cells.

The primary advantage to using arrays is processing speed. Reading and writing to ranges of cells in Excel is relatively very time-consuming. Reading and writing to arrays is much faster.

If you are concerned with speed and your code reads or writes large amounts of data to Excel, you should consider using Arrays.

You declare Arrays similar to regular variables, except you must also declare the size of the array:

Dim data_arr (1 to 5) as Long

Above we wrote "1 to 5", this tells VBA that our reference number for the items in the series are 1 through 5. Alternatively, you could write:

Dim data_arr (4) as Long

Why 4? Arrays by default start at 0. So when declaring array length in this manner you must subtract 1 (5-1=4). So, in this case, the first item in the series will be 0 and the last item will be 4.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

If you do use the second method, you can change VBA's settings to start arrays at 1 instead of 0. Make this declaration at the top of your module:

Option Base 1

This option only applies to the module where the declaration resides.

We recommend always defining the upper and lower boundaries of the array, using the first method that we discussed. By explicitly defining the ranges, you won't make the mistake of forgetting where the array starts.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Now that we have an array created:

Dim arr( 5 to 10) as string

We can assign values to the array:

Arr(5) = "Steve"

Arr(6) = "Jill"

Arr(7) = ""Bill"

Arr(8) = "Betty"

Arr (9) = "Scott"

Sub Macro1()

Dim arr(5 To 10) As String

End Sub

Imagine doing that for 100s of entries! Instead let's use a loop and read values from a range in Excel:

For n = 5 to 10

Arr (n) = cells(n-4,1).value

Next n

This will read values from range("a1:a6") and put them into the array.

Sub Macro1()

Dim arr(1 To 6) As Variant

End Sub

What if we want to pull values from the array? You can write the values to an Excel range, assign the values to a variable, or display a message box.One option isYou can assign values to a variable:

CEO_name = Arr(6)

Or display the value using a message box.

The previous examples only dealt with a single-dimension array, similar to a single row or column in Excel. Let's create an array with a second dimension:

Dim arr(1 to 5, 1 to 2) as variant

This will create a 5 row and 2 column array.

Sub Macro1()

End Sub

Now we can populate our 3 row and 4 column array from a range in Excel:

for x = 1 to 4

For y = 1 to 3

Arr(y,x) = Cells(y,x).value

Next y

Next x

Notice we need 2 different loops to populate the 2 different dimensions. We used x to move horizontally and y to move vertically.

We converted our Interactive VBA Tutorial into a 70 page PDF. The PDF is colorful, easy to navigate, and filled with examples. You'll also receive access to our PowerPoint and Word VBA Tutorials (Access and Outlook coming soon)!

Our free VBA Add-in installs directly into the VBA Editor, giving you access to 150 ready-to-use VBA code examples for Excel.

Simply click your desired code example and it will immediately insert into the VBA code editor.

This is a MUCH simplified version of our premium VBA Code Generator.

PDF "Cheat Sheet" containing the most commonly used VBA Commands and syntax. Print the PDF or save it to your computer for easy reference!

Thanks for Registering! Your account has been successfully created with us.

Your email address has been successfully verified! Your account is now active. You can now login to your account.

Do you want to resume , ? Press "Yes" to resume or "No" to go to the Home page.

Wait! If you continue, your progress will be deleted. Please create a free account to save your progress.

ContinueAfter installation, do you see this pop-up?

This means you installed the wrong version of AutoMacro(32-bit vs 64-bit). Please follow the directions to uninstall AutoMacro and download+install the correct version.

ContinueUltimate VBA Add-in

Ultimate VBA Add-in

Offer expires soon!

Sale Ends Friday at Midnight

VBA (Macros)

Code Examples Add-in

WAIT! if you continue your progress will be lost.

Please create a free account to save your progress:

continue in 7 seconds

Continue